What was the world like in the eighteenth century?

In the 1700s, countries were ruled by kings or other powerful leaders including emperors or sultans. In many countries such as Russia, the poorest people were owned by the richer people. However, new ideas about the rights of people began to spread in the eighteenth century. Many revolutions occurred.

In 1775, settlers in America went to war with the English. They wanted to set up a republic. In 1798, the people of France took power from the King and rich nobles.

Revolution in Ireland in 1798

In the eighteenth century, many people in Ireland were not happy with how Ireland was ruled by the king in England. Ireland had a parliament in Dublin, but most of the time it could only pass laws that the king of England agreed with.

When the American colonies broke free from England, some people hoped that Ireland would be able to become free from English rule also. People liked the ideas of liberty and equality, which they heard about during the French Revolution.

In 1791, a group called the United Irishmen were set up. They wanted Irish people of all faiths to unite and create an Irish Republic which would give rights to everyone. In 1798, they tried to defeat the British by starting a rebellion.

American War of Independence

In North America in the 18th century, there were thirteen states called colonies which were ruled by the king of England . There was a war between America and England from 1775 until 1783 called the American War of Independence. The American settlers were known as colonists and were led by George Washington.

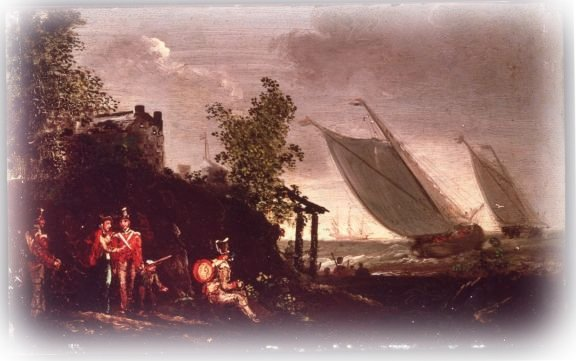

The british troops were known as 'redcoats'. They were not suited for war in the colonies as they could easily be spotted as targets.

America won this war and became a new country with its own government. The American rebels had been helped in the war by soldiers sent by the king of France.

The british troops were known as 'redcoats'. They were not suited for war in the colonies as they could easily be spotted as targets.

America won this war and became a new country with its own government. The American rebels had been helped in the war by soldiers sent by the king of France.

French Revolution

In 1789, a revolution began in France against the French king, King Louis XVI, and the rich nobles. This was known as the French Revolution. The king and queen and thousands of nobles were put to death and a new type of government, a Republic, was set up in France.

The following were the last words of King Louis XVI just before he was beheaded:

“I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I Pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France.”

After the execution of the king, France did not have a monarch again. The ideas of the French Revolution soon spread to other countries, including Ireland.

The following were the last words of King Louis XVI just before he was beheaded:

“I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I Pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France.”

After the execution of the king, France did not have a monarch again. The ideas of the French Revolution soon spread to other countries, including Ireland.

Why was there a rebellion?

There were many reasons why the rebellion of 1798 started in Ireland. One reason was that there was discrimination against certain religions and certain groups who were not rich. In the 1790s, groups such as the Presbyterians and the Catholics were denied many of their rights. At the time, the richest group, called the Ascendancy, were in power in Ireland. The Ascendancy were from the ruling classes. They were Protestant and had seats in the Irish Parliament.

Poorer people had no say in how the Irish Parliament worked, even though they made up most of the population. At that time, no Catholic could sit in Parliament or become a Member of Parliament (MP). Even though there was a Parliament in Dublin, most of the power was in London.

The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, with its ideals of liberty, equality and brotherhood, caused many Irish people to consider changes which could take place in Ireland to give everybody better rights. Laws known as the Penal Laws had brought discrimination against Catholics and Presbyterians, however these were ended in 1792 and 1793.

Another reason for unrest in Ireland was due to many secret societies which developed in the countryside and sought rights for farmers and other people who worked on the land. Some of the names of these groups were the ‘Whiteboys’ and ‘Peep O’ Day Boys’. Many of these groups went out at night and damaged the property of some landlords in their area. They wanted cheaper rents and better conditions for the people who worked on the land.

United Irishmen

The United Irishmen formed in 1791. The members wanted everyone in Ireland to be treated equally. At first the United Irishmen looked for changes in Parliament. Later they demanded that a separate republic should be set up in Ireland.

Crest of the United Irishmen

The United Irishmen designed a crest incorporating the harp to represent Ireland. The motto read as follows: Equality: it is new strung and shall be heard. This gave a clear warning to the authorities. The red cap of liberty, presented to freed Roman slaves, is included in the crest.

One of the leaders of the United Irishmen was a man named Wolfe Tone. He was a Church of Ireland lawyer from Dublin. Wolfe Tone was impressed by the French Revolution and looked for help from France and America to start a similar revolution in Ireland. However in 1793, a war broke out between England and France. This meant that anybody looking for help from France was seen as a traitor by the British government. In 1793, the United Irishmen was banned by the government and it was against the law to have anything to do with the United Irishmen. In 1794, many of the members of the United Irishmen were arrested.

Seal of the United Irishmen

This is a photograph of the seal of the United Irishmen, which was designed by Robert Emmet.Wolfe Tone

Wolfe Tone was one of the leaders of the United Irishmen. He was born in Dublin in 1763 and became a lawyer. He was a Protestant yet like many of the leaders of the United Irishmen he wanted to seek rights for his Presbyterian and Catholic countrymen.In 1795, Wolfe Tone left Ireland for America to escape arrest. He next went to France to ask for soldiers to help with a revolution in Ireland. In 1796, Wolfe Tone sailed from France to Ireland with a French general called General Hoche and a fleet of thirty-five ships and about 15,000 soldiers. However, the ships got caught in terrible storms. Some ships sank and the sailors were lost. Many French ships waited off Bantry Bay for calmer weather but in the end they returned to France.

French Landing at Bantry Bay

In late December 1796 Wolfe Tone and a fleet of about 43 ships with 15,000 men set sail from France towards Ireland with the intention of over throwing English rule. However, despite Wolfe Tone's preparations in France, the weather was victorious on this occasion. Before the ships could leave Brest harbour one ship had already been separated from the main fleet. During the night that followed, across the English Channel, 7 other ships separated from the main party. One of the 7 included the ship of General Hoche, one of the Commanders-in-chief of the rising. Bad weather continued splitting the fleet further and preventing Tone and his men from landing, resulting in only 7 'Sail of the line' or war ships and one frigate remaining after a week of bad weather in Bantry Bay. The rebellion was abandoned and Wolfe Tone returned to France.Wolf Tone’s diary shows how disappointed he felt about his unsuccessful attempt to land with French troops in 1796.

He wrote the following account on the 21st December 1796:

“There cannot be imagined a situation more provokingly tantalising than mine at this moment, within view, almost within reach of my native land, and uncertain whether I shall ever set foot in it..We were near enough to toss a biscuit ashore”

He wrote another account on the 26th December 1796:

“We have now been six days in Bantry Bay, within 500 yards of the shore, without being able to effect a landing…All our hopes are now reduced to getting back safely to Brest”

The ships had to return to France without a fight.

Yeomanry and Militia

Lord Edward Fitzgerald

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

The British army heard about the ships and they knew that the United Irishmen were planning a big fight. They decided to destroy the United Irishmen. They imprisoned many of the leaders of the movement and warned people to tell them about any United Irishmen that they knew.

The government tried to stamp out rebellion. They got information from many spies and posted notices warning people to hand over any weapons they had. Houses were searched, especially the homes of blacksmiths because they were known to make a weapon called a pike. Leaders of the rising were arrested.

The government needed more soldiers in Ireland to put down any fighting. In 1796, a group of soldiers called Yeomanry were set up. These were civilians who were put into groups as soldiers. There were also other soldiers who were forced to join a group called the militia. There were also paid soldiers from Germany who were known as Hessians.

The army inflicted terror on the countryside. Many ordinary people were flogged and tortured to punish them for supporting a rebellion against the king or to try to get information from them. Houses were burned and property was stolen or destroyed. Anyone suspected of being a rebel was shot. This cruel treatment by the army made many people join the fight against the government troops.

The main weapon of the rebels of 1798 was a long stick with a metal top called the pike. It was sharp and could cut the reins of horses. The pike was quite useful against cavalry but it was not as good against firearms.

The soldiers fighting against the rebels had guns. These were more powerful than the pikes used by most of the rebel forces. Many of the guns had a bayonet which could be attached.

An image of a 1798 rebel being whipped.

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

One of the main places where the rebellion of 1798 occurred was in County Wexford. The Catholic peasants were led by two local priests, Father John Murphy and Father Micheal Murphy.

One of the bloodiest battles of the 1798 rebellion was the battle of New Ross in June 1798 when the United Irishmen commanded by a local Protestant landlord, Bagenal Harvey, were defeated. Over 3,000 rebels were killed. The last battle was the battle of Vinegar Hill in Enniscorthy. The rebels were defeated and the towns of Wexford were recaptured by British troops.

There was also a rebellion in Ulster. One of the leaders of the United Irishmen in Ulster was a Presbyterian, Henry Joy McCracken. He was one of the founders of the United Irishmen. He captured Antrim town but was soon caught and hanged in Belfast. Henry Munro led the rebels in County Down but he too was defeated and hanged.

The British government decided to abolish the Irish Parliament in Dublin. In 1800, the Act of Union was passed and Ireland was then ruled from Westminster Parliament in London.

Anne Devlin was Robert Emmet’s housekeeper and from a well known rebel family. She was put in prison for three years with some of her family because of her connection to Robert Emmet. She remained loyal to Robert Emmet and the other rebels of 1803 and 1798. She refused bribes of money to give information or to become a spy for the government and did not even give in to the harsh treatment of the governor of Kilmainham Jail William Trevor. She is noted as a heroine and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetry in Dublin .

The village of Rathfarnham County Dublin has a statue erected to honour Anne Devlin. She once lived in Butterfield Avenue in Rathfarnham when she worked as Robert Emmet’s housekeeper. She also delivered many secret messages for Robert Emmet and helped him to plan the rebellion of 1803.

The government needed more soldiers in Ireland to put down any fighting. In 1796, a group of soldiers called Yeomanry were set up. These were civilians who were put into groups as soldiers. There were also other soldiers who were forced to join a group called the militia. There were also paid soldiers from Germany who were known as Hessians.

The army inflicted terror on the countryside. Many ordinary people were flogged and tortured to punish them for supporting a rebellion against the king or to try to get information from them. Houses were burned and property was stolen or destroyed. Anyone suspected of being a rebel was shot. This cruel treatment by the army made many people join the fight against the government troops.

Rebellion in 1798

The rebellion began in May 1798 in Kildare, however it soon spread to Meath, Wicklow and Wexford. In March 1798, sixteen of the leaders of the United Irishmen were arrested in Dublin . In May 1798, Lord Edward Fitzgerald, one of the leaders, was wounded and died. Many of the other important leaders of the United Irishmen were also captured.Weapons

Piking of prisoners by rebels on Wexford bridge, 20 June 1798

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

The main weapon of the rebels of 1798 was a long stick with a metal top called the pike. It was sharp and could cut the reins of horses. The pike was quite useful against cavalry but it was not as good against firearms.

The soldiers fighting against the rebels had guns. These were more powerful than the pikes used by most of the rebel forces. Many of the guns had a bayonet which could be attached.

An image of a 1798 rebel being whipped.

Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

1798 Rebellion in Wexford and Ulster

One of the main places where the rebellion of 1798 occurred was in County Wexford. The Catholic peasants were led by two local priests, Father John Murphy and Father Micheal Murphy.

By May 1798 the rebels had taken over the towns of Enniscorthy and Wexford. A republic was declared but it did not last as the rebels were soon beaten back by British forces.

The Battle of New Ross

One of the bloodiest battles of the 1798 rebellion was the battle of New Ross in June 1798 when the United Irishmen commanded by a local Protestant landlord, Bagenal Harvey, were defeated. Over 3,000 rebels were killed. The last battle was the battle of Vinegar Hill in Enniscorthy. The rebels were defeated and the towns of Wexford were recaptured by British troops.

Rebellion in Ulster

There was also a rebellion in Ulster. One of the leaders of the United Irishmen in Ulster was a Presbyterian, Henry Joy McCracken. He was one of the founders of the United Irishmen. He captured Antrim town but was soon caught and hanged in Belfast. Henry Munro led the rebels in County Down but he too was defeated and hanged.

The End of 1798

More help came from France but the rebels still did not win the rebellion. In August 1798, over 1,000 French soldiers landed at Killala Bay in Mayo under the command of General Humbert. At first they defeated the English forces, however folowing a lot of fighting, they later surrendered in September 1798.

The French Landing in Killala Bay

National Library of Ireland

National Library of Ireland

Another French force arrived off Tory Island in Donegal in September 1798 with Wolfe Tone on board. He was arrested and died soon afterwards in prison. The rebellion of 1798 was over. Rebels who were captured were seen as traitors to England. Large numbers of rebels were given life imprisonment sentences and transported to Botany Bay in Australia.

What happened as a result of the rising?

The British government decided to abolish the Irish Parliament in Dublin. In 1800, the Act of Union was passed and Ireland was then ruled from Westminster Parliament in London.

The Rebellion of 1803

Rebellion and Robert Emmet

Many people in Ireland did not want a union with Britain in 1801. Some people looked for support from France for another rebellion after 1798 but they failed to get this support. In 1803, another rebellion started in Ireland. This time it was centred around Dublin but it did not receive enough support at the time. The rebellion failed and the leader Robert Emmet was executed after he was found guilty of high treason. On the 20th September 1803, Robert Emmet was taken from Kilmainham Jail to a place opposite St Catherine's Church in Thomas Street and was hanged.

Anne Devlin

Anne Devlin was Robert Emmet’s housekeeper and from a well known rebel family. She was put in prison for three years with some of her family because of her connection to Robert Emmet. She remained loyal to Robert Emmet and the other rebels of 1803 and 1798. She refused bribes of money to give information or to become a spy for the government and did not even give in to the harsh treatment of the governor of Kilmainham Jail William Trevor. She is noted as a heroine and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetry in Dublin .

The village of Rathfarnham County Dublin has a statue erected to honour Anne Devlin. She once lived in Butterfield Avenue in Rathfarnham when she worked as Robert Emmet’s housekeeper. She also delivered many secret messages for Robert Emmet and helped him to plan the rebellion of 1803.

No comments:

Post a Comment